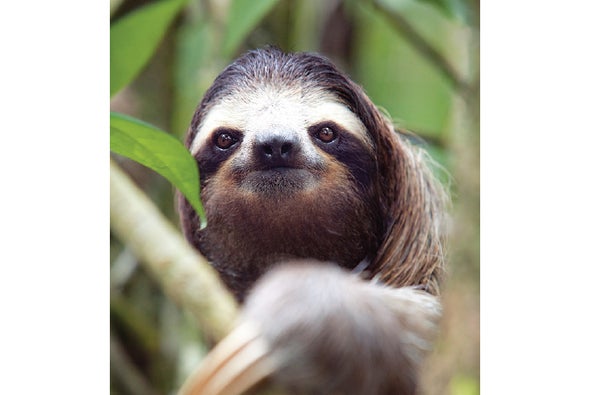

Sloths Pictures

The true stories behind these famous baby sloth photos. With a following rivaling that of the Kardashians, these baby sloths will never know just how famous they have become. Note: Many of these baby sloths were photographed in rescue centers. SloCo is not a rescue center but we work closely with wildlife rehabilitation organisations on. Download 4,817 sloth free vectors. Choose from over a million free vectors, clipart graphics, vector art images, design templates, and illustrations created by artists worldwide!

- Download Sloth stock photos. Affordable and search from millions of royalty free images, photos and vectors.

- Super coloring - free printable coloring pages for kids, coloring sheets, free colouring book, illustrations, printable pictures, clipart, black and white pictures, line art and drawings. Supercoloring.com is a super fun for all ages: for boys and girls, kids and adults, teenagers and toddlers, preschoolers and older kids at school.

- The 29 Cutest Sloths That Ever Slothed The genius behind a 'bucket of sloths' has published a book called The Power of Sloth, along with the ULTIMATE collection of sloth pictures. We can't handle.

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

Join Britannica's Publishing Partner Program and our community of experts to gain a global audience for your work!

Sloth, (suborder Phyllophaga), tree-dwelling mammal noted for its slowness of movement. All five living species are limited to the lowland tropical forests of South and Central America, where they can be found high in the forest canopy sunning, resting, or feeding on leaves. Although two-toed sloths (family Megalonychidae) are capable of climbing and positioning themselves vertically, they spend almost all of their time hanging horizontally, using their large hooklike extremities to move along branches and vines. Three-toed sloths (family Bradypodidae) move in the same way but often sit in the forks of trees rather than hanging from branches.

What kind of animal is a sloth?

Sloths are mammals. They are part of the order Pilosa, which is also home to anteaters. Together with armadillos, sloths and anteaters form the magnorder Xenarthra.

How many types of sloths are there?

A total of five species of sloths exist: the pygmy three-toed sloth, the maned sloth, the pale-throated three-toed sloth, the brown-throated three-toed sloth, and Linnaeus's two-toed sloth. All sloths are either two-toed or three-toed.

Where do sloths live?

Sloths live in the lowland tropical areas of South and Central America. They spend most of their life in the forest canopy. Two-toed sloths tend to hang horizontally from branches, while three-toed sloths often sit in the forks of trees.

What do sloths eat?

Sloths are omnivores. Because they spend most of their time in trees, they like to munch on leaves, twigs, flowers, and other foliage, though some species may eat insects and other small animals.

Why are sloths so slow?

Sloths are slow because of their diet and metabolic rate. They eat a low-calorie diet consisting exclusively of plants, and they metabolize at a rate that is only 40–45 percent of what is expected for mammals of their weight. Sloths must move slowly to conserve energy.

Sloths have long legs, stumpy tails, and rounded heads with inconspicuous ears. Although they possess colour vision, sloths’ eyesight and hearing are not very acute; orientation is mainly by touch. The limbs are adapted for suspending the body rather than supporting it. As a result, sloths are completely helpless on the ground unless there is something to grasp. Even then, they are able only to drag themselves along with their claws. They are surprisingly good swimmers. Generally nocturnal, sloths are solitary and are aggressive toward others of the same sex.

Sloths have large multichambered stomachs and an ability to tolerate strong chemicals from the foliage they eat. The leafy food is digested slowly; a fermenting meal may take up to a week to process. The stomach is constantly filled, its contents making up about 30 percent of the sloth’s weight. Sloths descend to the ground at approximately six-day intervals to urinate and defecate (see Sidebar: A moving habitat). Physiologically, sloths are heterothermic—that is, they have imperfect control over their body temperature. Normally ranging between 25 and 35 °C (77 and 95 °F), body temperature may drop to as low as 20 °C (68 °F). At this temperature the animals become torpid. Although heterothermicity makes sloths very sensitive to temperature change, they have thick skin and are able to withstand severe injuries.

All sloths were formerly classified in the same family (Bradypodidae), but two-toed sloths have been found to be so different from three-toed sloths that they are now classified in a separate family (Megalonychidae).

Three-toed sloths

The three-toed sloth (family Bradypodidae) is also called the ai in Latin America because of the high-pitched cry it produces when agitated. All four species belong to the same genus, Bradypus, and the coloration of their short facial hair bestows them with a perpetually smiling expression. The brown-throated three-toed sloth (B. variegatus) occurs in Central and South America from Honduras to northern Argentina; the pale-throated three-toed sloth (B. tridactylus) is found in northern South America; the maned sloth (B. torquatus) is restricted to the small Atlantic forest of southeastern Brazil; and the pygmy three-toed sloth (B. pygmaeus) inhabits the Isla Escudo de Veraguas, a small Caribbean island off the northwestern coast of Panama.

Although most mammals have seven neck vertebrae, three-toed sloths have eight or nine, which permits them to turn their heads through a 270° arc. The teeth are simple pegs, and the upper front pair are smaller than the others; incisor and true canine teeth are lacking. Adults weigh only about 4 kg (8.8 pounds), and the young weigh less than 1 kg (2.2 pounds), possibly as little as 150–250 grams (about 5–9 ounces) at birth. (The birth weight of B. torquatus, for example, is only 300 grams [about 11 ounces].) The head and body length of three-toed sloths averages 58 cm (23 inches), and the tail is short, round, and movable. The forelimbs are 50 percent longer than the hind limbs; all four feet have three long, curved sharp claws. Sloths’ coloration makes them difficult to spot, even though they are very common in some areas. The outer layer of shaggy long hair is pale brown to gray and covers a short, dense coat of black-and-white underfur. The outer hairs have many cracks, perhaps caused by the algae living there. The algae give the animals a greenish tinge, especially during the rainy season. Sexes look alike in the maned sloth, but in the other species males have a large patch (speculum) in the middle of the back that lacks overhair, thus revealing the black dorsal stripe and bordering white underfur, which is sometimes stained yellow to orange. The maned sloth gets its name from the long black hair on the back of its head and neck.

Three-toed sloths, although mainly nocturnal, may be active day or night but spend only about 10 percent of their time moving at all. They sleep either perched in the fork of a tree or hanging from a branch, with all four feet bunched together and the head tucked in on the chest. In this posture the sloth resembles a clump of dead leaves, so inconspicuous that it was once thought these animals ate only the leaves of cecropia trees because in other trees it went undetected. Research has since shown that they eat the foliage of a wide variety of other trees and vines. Locating food by touch and smell, the sloth feeds by hooking a branch with its claws and pulling it to its mouth. Sloths’ slow movements and mainly nocturnal habits generally do not attract the attention of predators such as jaguars and harpy eagles. Normally, three-toed sloths are silent and docile, but if disturbed they can strike out furiously with the sharp foreclaws.

Reproduction is seasonal in the brown- and pale-throated species; the maned sloth may breed throughout the year. Reproduction in pygmy three-toed sloths, however, has not yet been observed. A single young is born after less than six months’ gestation. Newborn sloths cling to the mother’s abdomen and remain with the mother until at least five months of age. Three-toed sloths are so difficult to maintain in captivity that little is known about their breeding behaviour and other aspects of their life history.

- related topics

The sluggish creature crept along a tangle of vines towards us. I watched, half-listening to our night walk guide as he identified the grey furry shape as a brown-throated three-toed sloth. The rest of the group giggled at its slow, clumsy movements, but I knew that for a sloth this was practically a flat-out Olympic sprint. And with each clambering movement it was coming closer and closer to us. And to the ground.

“I think it’s coming down!” our guide said, his voice growing more and more excited.

“Oh my god…” I whispered, half-strangled with disbelief. Our guide looked at me, and we realized that we were thinking the exact same thing.

“Do you think it’s going to… ?”

“But it’s so rare, what are the odds that we would… Oh my god.”

By this point the sloth was just a few meters away, likely breaking some sort of sloth record for fastest descent. There was absolutely no mistaking what was about to happen.

This sloth was about to poop. And we were going to watch.

When Defecation Is Deadly

The brown-throated sloth (Bradypus variegatus) is one of two sloth species found in Costa Rica. They live mostly solitary lives high in the forest canopy, with small home ranges of about 5.5 hectares, or a little more than 5 soccer fields.

Related Articles

- Fantastic Fecal Phenomena of the Animal World By Justine E. Hausheer

Adorable as they are, you might think twice about wanting to snuggle a sloth. All three-toed sloths have unique hair with cracks along the surface that absorb water to nourish colonies of hydroponic algae. These fur gardens — which often give the sloth’s fur a greenish tinge — also house multiple species of arthropods and fungi.

Despite what we humans would consider highly questionable personal hygiene habits, sloths are incredibly fussy poopers. Hanging upside down isn’t necessarily the best angle from which to enjoy the Sunday paper in privacy, if you know what I mean. So every time a three-toed sloth needs to defecate it makes the slow, arduous journey down from the canopy and onto the forest floor, where it poops below the same tree every time.

Scientists aren’t exactly sure why three-toed sloths stick to the same tree, but it’s possible that they use these latrines to communicate with other sloths, avoid detection from predators, or even as a means of fertilizing their favorite trees.

Three-toed sloths cut down on the inconvenience by only pooping an average of once every week, a frequency that would have most of us downing laxatives and praying for death. Infrequent pooping is normal for sloths, which eat toxic leaves from just a few species of trees and have the slowest rate of digestion of any mammal species. We were patrolling a tiny patch of cloud forest for just two hours on one night, so to stumble on a sloth making its pre-potty descent was preposterously lucky.

Infrequent bowel movements are also a built-in safety feature. Sloths are an easy fast-food meal (pun intended) for numerous predators, but they’re much safer when camouflaged in the canopy. It’s a different story on the ground, where research shows an estimated 50 percent of sloths meet an untimely end. It’s bad enough to have a jaguar pounce on you, but it’s even worse when they pounce mid potty break.

Traveling down from the canopy also burns a lot of energy for slow-moving sloths, and scientists estimate that each trip costs a sloth about 8 percent of its daily energy needs.

The tradeoff for this infrequent schedule is that by the time a sloth is ready to go, they have quite a backlog of, ahem, inventory waiting to move. Scientists estimate that with each dump, sloths lose about one-fifth of their body weight. ONE-FIFTH. That’s the equivalent of a 150-pound person leaving a 30-pound poop.

Caught in the Act

By this point the rest of the group had figured out that we were about to see something special, even if they weren’t exactly sure why I was literally jumping up and down. We stood quietly as the sloth swung down the last few feet of vine, descending head first before plopping awkwardly onto the forest floor.

It righted itself, sitting on the ground and grasping the vine with each of its front claws. Then it began to wiggle, rustling its posterior around in the leaf litter in front of an audience of 30 tourists trying desperately (and unsuccessfully) not to giggle.

After a few seconds our guide very thoughtfully turned off his spotlight to allow the poor creature a shred of privacy. There was a full moon, so we still had a pretty decent view of the continued wiggling and straining. After about 10 seconds of this bottom boogie the sloth heaved itself upward and began slow-motion racing back up the vine, without a backward glance.

Sloths Pictures Animated

The spotlight clicked back on, and we saw the little grey sloth bum receding back up to the treetops. Our guide looked at me, grinning, and said “Go for it.” I shot off towards the poo pile, camera in hand, as he filled the rest of the group in on what we had just seen.

Nestled amidst the leaves was a pile of little brown nuggets, each the size of a cherry tomato. Given the size of the deposit I suspected that our little friend hadn’t quite fulfilled his mission, and with an audience of 30 people I don’t blame him.

Moths, Sloths and Symbiosis

After taking a few pictures of the sloth poo, I grabbed a stick and began prodding the pile in search of moths. Yes, moths.

When a sloth descends to earth to poo, female pyralid moths crawl out of the sloth’s fur and lay their eggs in the poo pile. The moth larvae feed on the decaying sloth excrement, and once they develop into adults they fly back into the canopy in search of a new sloth to live on.

Clearly the moths have got it made, but do the sloths benefit from this relationship? To get to the bottom of the mystery (pun intended), American scientists captured sloths from two different species in Costa Rica. The brown-throated three-toed sloth, like the one I had just seen do the deed, always poops on the ground. But the Hoffman’s two-toed sloth isn’t as picky and will also poop from the canopy. (Heads up!)

The scientists used a small vacuum to suck up all of the moths they could find on each sloth. They also took hair samples to see if there were differences in the fur microbiota and chemical makeup between species.

They discovered that three-toed sloths have more moths, and that more moths corresponds to higher levels of nitrogen and algae in the fur. The researchers think that the moths are somehow increasing nitrogen levels, which acts as a fertilizer for the algae.

So what’s the benefit for the sloths? We’re still not sure.

The researchers theorized that the algae might provide a mobile source of additional nutrition for the sloths. But until someone documents widespread self-licking amid the sloths, it’s not clear how extra nutrients in the fur would make their way into the sloth’s diet. What is clear, though, is that the moths alter the furry biome of their mobile sloth homes.

Sloths Pictures

Unfortunately, no moths emerged from the still-glistening pile of sloth poo, despite my thorough prodding. The beleaguered sloth was back in the canopy, and it was time to move on to see what other wildlife we could find in the forest this night.

Sloths Pictures Funny

But one thing was for sure: I was never going to look at a sloth the same way again.